0. Overview | 1. Student Profiles | 2. Discipline Contexts | 3. Media Choices | 4. Intended Learning Outcomes | 5. Assessment | 6. Learning Teaching Activities | 7. Feedback | 8. Evaluation

The third element in a constructively aligned course design and the sixth stage of the 8-SLDF are the learning activities that prepare students for the assessment of their learning outcomes. This is not about the content that we share with our students; it is about how we develop an appropriate strategy to do that. Some courses will require novice learners to acquire a good deal of knowledge, and a set-text and discursive seminars may be the appropriate strategy. Could we use one-minute papers, ‘Pecha Kucha’, lightning talks, and other techniques to secure student engagement? Alternatively, we might be designing a more advanced course in which a discovery learning approach is more appropriate. Could we use enquiry-based learning models here instead, asking our students to prepare to take a debate position, run a Moot or team-based discussion? The important thing is that we are developing a strategy and practical approaches that build on our design, not seeking innovation for innovation’s sake.

Preparations

It is likely that as you begin your design discussions, you will be full of good ideas and a list of things you want to avoid! You also probably have a clear idea of WHAT your students need to know. The processes outlined in this briefing note take a slightly different perspective. It focuses on what a student needs to be able to DO upon completing your course. The focus is on mapping ILOs to Session Objectives and ensuring that the activities designed are closely mapped.

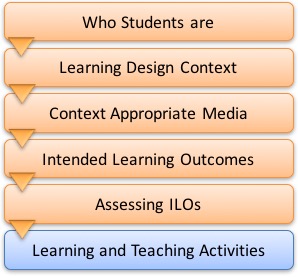

The guidelines are based on the assumption that you have already followed the previous stages in this Learning Design Framework. If you haven’t, you may find it difficult to reconcile the guidance with your existing practice (and assumptions). It is also worth reminding you that the guidance notes are aimed at the level of courses and programmes, not as a quick source of ideas for a specific session. The stages you should have covered to get to this point are:

What follows is, therefore, guidance for frameworks and models for how to go about putting together learning and teaching activities that are fit for purpose:

- That meet the expectations and orientations of your students (1/8-SLDF)

- That takes into account the discipline context (2/8-SLDF)

- They leverage appropriate media and technology support (3/8-SLDF)

- The enable students to demonstrate that they have the ability to evidence achievement against the ILO (4/8-SLDF)

- That they serve as ‘rehearsals’ for assessment tasks (5/8-SLDF)

Developing a Learning and Teaching Strategy

Module and Programme specifications are written with a learning and teaching strategy at their core. This should not be seen as a procedural obligation but rather as an opportunity to define the nature of your students’ learning experience.

Your strategy should be articulated in writing. The course design team should agree that it represents their collective view of good practice at the appropriate level, for those students and that discipline. Strategies, both at module and programme level, should be firmly grounded in the Intended Learning Outcomes. As you will have seen in 4/8-SLDF, there is a particular structure for stating the aims of a programme or module and of elaborating the ILOs.

It should be possible to ‘infer’ from the wording of the ILOs what the learning and teaching strategy is likely to be. At this stage of the design, we can begin to break down the structure of our module (outlined in the ILOs) into a more pragmatic context, grounded in the realities of timetabling and scheduling.

If we take the UK’s QAA guidance on notional student learning (NSL) into account, it suggests that each academic credit broadly equates to 10 hours of student learning. This would mean that a 20-credit course would anticipate a student undertaking 200 hours of study. This time allowance should include everything: tutorials, webinars, and reading time. In-class contact time, reading time, reflection time, and assessment. There are detailed planning tools to help you do this if required (See SOLE), although, as a design team, you should be able to manage the process with an Excel spreadsheet or an A3 sheet and coloured pens!

Clearly, the structure of a 30-credit course taught over 22 weeks will differ from that of a 15- or 20-credit course taught over 10 or 12 weeks.

I would suggest that you think of a ‘Session’ as a sub-unit of a week or topic. Everything asked of a student during that week or topic should be able to be mapped to a course ILO. When a student asks, ‘Why am I doing this?’ they deserve to have an answer.

If you have articulated well-structured and meaningful ILOs across all five domains of learning you will find it relatively straightforward to craft a set of week by week, or topic by topic, session objectives. Remember, outcomes are ultimately assessed, and objectives are not.

Patterns of Learning

I do not regard learning design as a science, despite the best efforts of machine learning advocates over the last 70 years. Neither is it a ‘Dark Art’, to be left to individuals behind closed doors, developing their course solely based on their personal expertise. Learning design is both science and art; it is a craft.

Each module should be a blend of knowledge, skills and abilities. Ideally, attention should be paid to all five domains of learning to ensure there is balance in the educational experience. While it is not always possible to reflect all domains, we should avoid the temptation to focus on ‘content’ and intellectual skills, then sprinkle a few engagement activities and call that ‘skills’ development.

Here are some examples of how learning patterns can be defined and visualised.

Explore each of these four courses. Each numbered block refers to a well-structured ILO. Each colour corresponds to the educational domain that the ILO maps against. So, for example, module (A) contains four epistemological (metacognitive-blue) ILOs, and one each of Intellectual (cognitive-orange), Professional (affective-red) and Communication (interpersonal-green). Contrast that with (C), which has just one each of epistemological, intellectual and professional skills but three communication skills. Which style of modules, or learning and teaching strategy, do you anticipate these patterns might reflect?

Even without knowing the level or the discipline, we can infer something about the purpose or nature of each course (Atkinson, 2015).

A: Is clearly a foundational course in a new area of study for the student. There is a great deal of knowledge ‘content’ that needs to be conveyed. This is filtered through a distinct intellectual skill, mapped to a professional skill and some model of communication is required to check student attainment.

B: Is a balanced, but more advanced course. Clearly not a first-semester Level 7 or a Level 4 course. It has two epistemological outcomes, building on prior knowledge, three intellectual skills (the dominant theme of the course) and one each of professional, practical and communication skills. This is the pattern one might expect to see in a later course in a taught master’s programme or a Level 6 programme where a degree of independent study is assumed.

C: As mentioned, the emphasis in this course is clearly on communication or interpersonal skills. It might be an advocacy style course, or a communication skills course where the focus is on performance or presentational skills

D: Our final example has three outcomes designated as practical skills (psychomotor domain) and one of each other domains. The stress of this course is likely to be either a tool manipulation module (SPSS for Statistics or C++ Programming) or a physical pursuit (body manipulation, dance, sports, etc)

You may want to consider the pattern of your existing modules. Do they make sense in the context of the programme? Which domains of learning are absent?

Developing and structuring learning objectives

As a design team, you may want to give faculty the freedom to interpret the ILOs and how to teach them. Very often, though, in order to ensure a high-quality distributed model is effective, we require planning to be centralised. This means having a consistent week-by-week, or topic-by-topic, approach to the student learning experience.

One way to achieve this and ensure that all ILOs are taught is to map Session Objectives to ILOs. Let’s explore this process

- We begin with the ILOs for our course (already mapped to the Programme ILOs). This appears as column (B) on the left above, with eight ILOs covering all five domains of learning (colour coded)

- We then discuss, as a course team, the optimal sequencing of these ILOs. Inevitably, this won’t be a perfect fit, and some will be ‘whole module’ ILOs but persist. What does a student need to begin to master in order to tackle what follows? It’s not unusual, for example, to front-load a module with knowledge ILOs.

- Then we have a course team discussion about the relative weighting of each ILO. This means revisiting their work on the previous assessment design, but it’s a worthwhile step. Don’t assume that all ILOs have the same importance.

- We begin with the ILOs for our course (already mapped to the Programme ILOs). This appears as column (B) on the left above, with eight ILOs covering all five domains of learning (colour coded).

The focus is still on what students will be able to do rather than on the content that we need students to engage with. Skills and attributes are best delivered within a discipline context, and the aims and objectives of the modules and programme will determine that context.

ExampleLet’s look at an example drawn from 4/8-SLDF. Let’s assume this is a Level 5 Business Model with a metacognitive outcome ILO that states students will be able to: “Situatea range of theoreticians and their work in relation to globalisation” Remember that is what will be assessed. So, we are free to set learning objectives (not necessarily assessed) that might say students will engage in:

What’s important is to remember that the session objectives will not be directly assessed, so the following year or as a result of a change of faculty you might use the exact same ILOs taught with modified session objectives so that a metacognitive ILO that states students will be able to: “Situate a range of theoreticians and their work in relation to globalisation.” Now has a set of session teaching objectives that might say students will engage in:

The student experience from one year to the next would be very different (as different perhaps as between equivalent qualifications in different institutions), but the student will still be assessed on their ability to evidence the same ILOs, NOT their content recollection. |

Weighing Session Objectives

I would suggest that it is advisable to have no more than five objectives per session (topic or week). Ideally, you would have clear objectives mapped to an appropriate ILO’s domain. If the focus in a single session is entirely on Interpersonal skills, for example, there may be only one session objective. In the illustration below, over 11 sessions (topics or weeks). You can see a shifting balance of teaching focus throughout a module.

Following on from our earlier example, in Session 3, for example, one might expect objectives such as:

- Examine Liberalism and the work of Locke (metacognitive)

- Searching and validating data sources (psychomotor)

- Building an annotated bibliography using bibliographic software (psychomotor)

Contrast that with session objectives for session 7, where the emphasis is on intellectual skills and some professional skills:

- Construct a representation of economic data that supports the notion that globalisation is a net positive (cognitive)

- Challenge the established position of the World Economic Forum with respect to globalisation (affective)

You may decide this is too restrictive, but it is a great way to generate your ‘indicative content‘ in the specification document, ensuring consistent and well-balanced coverage of all the knowledge and skills determined by the ILOs and the assessment.

Learning Activities Design Template

Whether it is a course design team or an individual faculty member with primary responsibility for designing sessions (topics or weeks), it is helpful to take a consistent approach. My SOLE Model and Toolkit provides a detailed tool to support this design process, but simpler paper-based alternatives are available.

What follows is an example template for Session Planning, which in turn serves as a tool for planning learning activities. You may choose to design your own. Everything in a shaded area is the template; everything blue and bold has been annotated on the template.

The completed template above serves solely as one possible format for ensuring that a session, topic, or week of learning is covered appropriately. Mapping session objectives to ILOs and ensuring that a session covers more than just the content is important.

The actual activities deployed in the classroom and online are highly contextualised, and it is impractical and can be misleading to share specific ‘lesson ideas’. You will benefit most by talking to colleagues and educational developers in your institution.

Summary

- The content to be taught should serve the students’ ability to evidence the ILO

- The skills and attributes taught at a topic, week, or session level should be designed to rehearse elements of the assessment.

- Not everything that engages students is directly assessed, but everything they are asked to do should be justifiable as informing the assessment and ILOs.

You might want to ask yourself as a course design team

- How closely are the ILOs mapped to each topic, week, or session outline?

- How confident are you that you cover the ILOs appropriately in terms of weighting and importance?

- How much variation is there in the learning approaches taken throughout your module?

- How are you enabling students to develop skills beyond knowledge acquisition?

Now we move on to Stage 7 of the 8-SLDF, which looks at feedback.

References

Atkinson, S. (2011). Embodied and Embedded Theory in Practice: The Student-Owned Learning-Engagement (SOLE) Model. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12 (2), 1-18

Atkinson, S. (2015 Jul 9) Graduate Competencies, Employability and Educational Taxonomies: Critique of Intended Learning Outcomes Practice and Evidence of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education [Online] 10 (2) pp 154-177.